Advocating for the elimination of derogatory and racist mascots and images has been a part of NCAI’s mission throughout most of the organization’s history. While some critics of these efforts claim recent efforts are a result of a fad or fall into the recent “cancel culture” ideology, the reality is that NCAI’s work in this area has been ongoing for decades, with the goal of eradicating racist stereotypes and promoting a true and accurate representation of American Indian and Alaska Native people.

It may come as a surprise to our readers that we first see the mention of addressing negative stereotypes and images in 1950, at the onset of a decade most commonly associated with conformity and acceptance of the status quo. That year, at the 7th NCAI Annual Convention held in Bellingham, Washington, the organization first went on record to address the issue of misleading, inaccurate and harmful images. Resolution Number 49, “Calling for an End to Negative Portrayals of Indians,” was a short but succinct statement, requesting that film producers, the press, the entertainment industry, institutions of higher learning, AND individuals aim to depict Indians in a true-to-life manner. It is not a coincidence that NCAI first began its advocacy at this time in history. In 1950, televisions had just entered American homes and, by the end of the decade, they were a common household fixture. The movie industry was booming with packed theaters and Americans were well into their obsession with cinematic super stars. NCAI leaders knew that the entertainment industry had a captive audience upon which to impose its racist stereotypes. It was a critical time to redefine the Indian image.

So just how did NCAI spring into action? By monitoring the entertainment industry, rather than rejecting it all together, they collaborated with Hollywood to change the image being depicted of Native peoples. NCAI’s goal was to ensure quality TV programs and movies that displayed accurate depictions of Native life and culture, both historically and in the present day. Serving as a de facto consultant to the entertainment industry, NCAI weighed in on potential productions and provided suggestions on how to improve the overall depiction of American Indian and Alaska Native peoples.

As an example, in 1967, after ABC announced the airing of a multi-part TV show on George Armstong Custer, NCAI—along with other advocacy groups—voiced opposition to the series as the script perpetuated myths and told an untruthful version of historical events. In the Summer 1967 issue of The Sentinel, NCAI issued a scathing review of the Custer series. Writers exclaimed, “You may not realize it friends but an old enemy is coming back to life this Fall to renew the false myths about Indian people. For nearly 50 years, American Indians have struggled to overcome the stereotype of the renegade savage who preys on poor defenseless civilized white settlers who are peacefully trying to farm the new land…”

NCAI leaders encouraged allies to write letters to the network to express their outrage at the series, going so far as to provide the address for the President of ABC in The Sentinel. NCAI leaders went on to say, “The series must NOT go on TV. It would cause irreparable damage to the image of Indians as human beings.” Unfortunately, the series did air. However, as critiques of the show mounted, the network eventually decided to pull the series from television after just a few months.

NCAI continued its collaboration with the entertainment industry by consulting on programs that were depicting Indians with racist and harmful stereotypes. Serving as the watchful eye of Indian Country, NCAI also established relationships with executives and producers, and provided feedback on shows and movies when they were in the early development stage.

“Isn’t it time to stop perpetuating the stereotype and give both children and adults the true picture of Indian Culture and history?”

— NCAI Executive Director John Belindo (Kiowa Tribe, Navajo Nation), 1968

Although their efforts did yield some success, NCAI leaders realized they were fighting an uphill battle in a profit-driven industry where success in the box office often ruled out ethical considerations. Something had to change, and that something was public opinion. But NCAI leaders pondered: How could NCAI fight centuries of prejudice and racism entrenched in the minds of Americans and wrestle back ownership of the Indian image from non-Natives who designed and controlled a false portrayal of American Indian and Alaska Native peoples for their own benefit? Educating the public was the answer. NCAI soon turned its attention to placing a greater emphasis on information and awareness, and then expanded their platform to political advocacy on a larger, national scale.

In 1968, NCAI Executive Director John Belindo (Kiowa Tribe, Navajo Nation) served as the spokesperson for this effort. In a speech, he asked the question, “Isn’t it time to stop perpetuating the stereotype and give both children and adults the true picture of Indian Culture and history?” He then declared that Indian Country was prepared to launch a political movement to fight negative stereotypes and that NCAI would be at the lead. This position became official NCAI policy at the 25th NCAI Annual Convention held in Omaha, Nebraska. There, NCAI delegates adopted Resolution Number 17, “Public Information–Indian Image”, calling upon state departments of education, public agencies charged with education, and other Native organizations to eliminate “inaccurate, distorted and unfavorable literature and other material about Indians.” These images, the resolution stated, contributed to “anti-indian prejudice and bigotry” and must be eradicated.

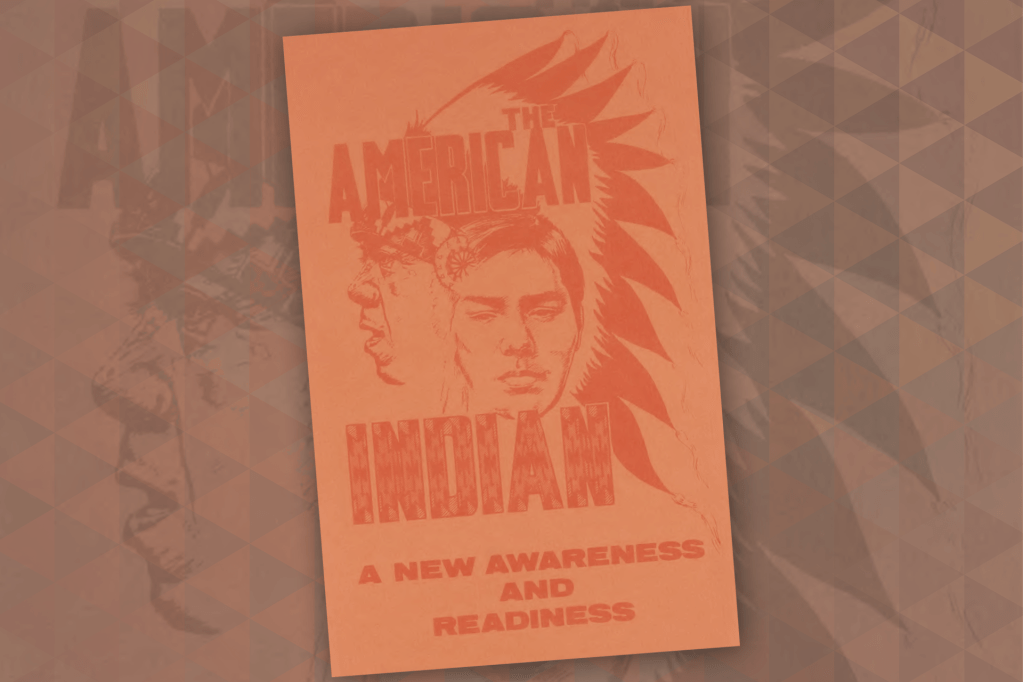

Then, in 1969, with John Belindo at the helm, NCAI launched a public education campaign, “The American Indian: A New Awareness and Readiness”, designed to combat inaccurate and damaging stereotypes and images of American Indians in the media. In March of that year, the organization kicked off the campaign with a press conference in the epicenter of the entertainment industry—Los Angeles.

The campaign featured television and radio public service announcements on Native culture and people. Vivid billboards adorned highways in nine U.S. cities, and depicted a traditional and modern image, with an arrow pointing towards the future. NCAI established the American Indian Media Service Committee, or AIMS, to “help eliminate the false, derogatory and harmful publicity which so often appears about the Indian in the nation’s mass media and to work towards a more accurate and positive portrayal of the Indian and his way of life.” The Executive Component of the committee was composed of tribal representatives, who worked alongside an Advisory Council of media professionals.

In the ensuing years, The Sentinel served as a sounding board for people all across the country. Readers with watchful eyes and open ears penned letters of concern and outrage calling attention to products, books, movies, and television shows featuring derogatory images of Indians. They reported racist stereotypes in the news, entertainment, educational, and literary worlds. One concerned reader expressed dismay about television’s portrayal of Indians, especially in regard to children’s programming. “May I request that you start changing that image right at the start—with children. One of today’s main mediums where children get their ideas and impressions is television. These ideas and impressions are carried into school and sometimes through adulthood. Have you watched children’s cartoons lately? On any day do so, and you will see a breeding ground for fostering ignorance about Indians.” The Sentinel had become the watchdog for Indian Country.

Moving into a new phase of its advocacy in the following years, NCAI expanded its campaign to the legislative arena. A number of resolutions were adopted that called for legislation to remove harmful stereotypes from educational institutions, the media, and sports. But by the 1990s, expanding upon this tradition of advocacy, NCAI turned its attention to focus heavily on racist and harmful mascots used in K-12 schools, colleges, and by professional sports teams.

In 1993, at the 50th NCAI Annual Convention held in Reno, Nevada, NCAI adopted a resolution declaring rightfully that negative harmful stereotypes were a human rights violation. Calling for an end to nicknames, mascots, and images, they took direct aim at the sports industry, colleges and universities. Two years later, gathering strength by joining forces, they created an Inter-Tribal Advisory Board on Mascots. By the end of the 1990s and into the 2000s, NCAI adopted many resolutions that further refined the organization’s advocacy on harmful mascots. Some of these statements condemned specific sports team franchises, and others took on the NCAA and professional sports leagues. This advocacy has continued to the current day and, although there is much more work to be done, it has resulted in successes on the K-12, state and professional sport levels. If you would like to learn more about this subject and stay up-to-date on recent news about the removal of harmful sports mascots, please consult the Ending the Era of Harmful Indian Mascots, website at ncai.org/proudtobe.