For this month’s blog post, we travel back in time to the Fourth Annual NCAI Convention held in Santa Fe, New Mexico, in December 1947 to share an inspirational story of unity and cooperation. The theme of this convention was “One for All, All for One, United We Endure”, an appropriate message carefully chosen by NCAI leaders to forge unity among the members of the young organization and also to position it for growth in the ensuing years.

There were many issues of importance on the agenda. The meeting occurred during a time in history that many say coincides with a shift in the federal government’s policy toward American Indians and Alaska Natives. Termination loomed as a threat to the existence of Tribal Nations everywhere, and recent proposals to disestablish reservations and tribal governments, and assimilate Native peoples into mainstream society were at the forefront of convention discussions that year.

In his address to the Convention, NCAI’s President at the time, Napoleon B. Johnson stated, “We are here united, all speaking for one, any one of us prepared to stand and speak for all. In this is our Indian creed, our concern for the preservation of all our people. The significance of our meeting lies in this, and nothing more.” He then explained how NCAI had spent the past year defending American Indian and Alaska Native people against proposed discriminatory legislation in Congress, against attempts to overtake their natural resources and economic interests, and against disenfranchisement of Native voters.

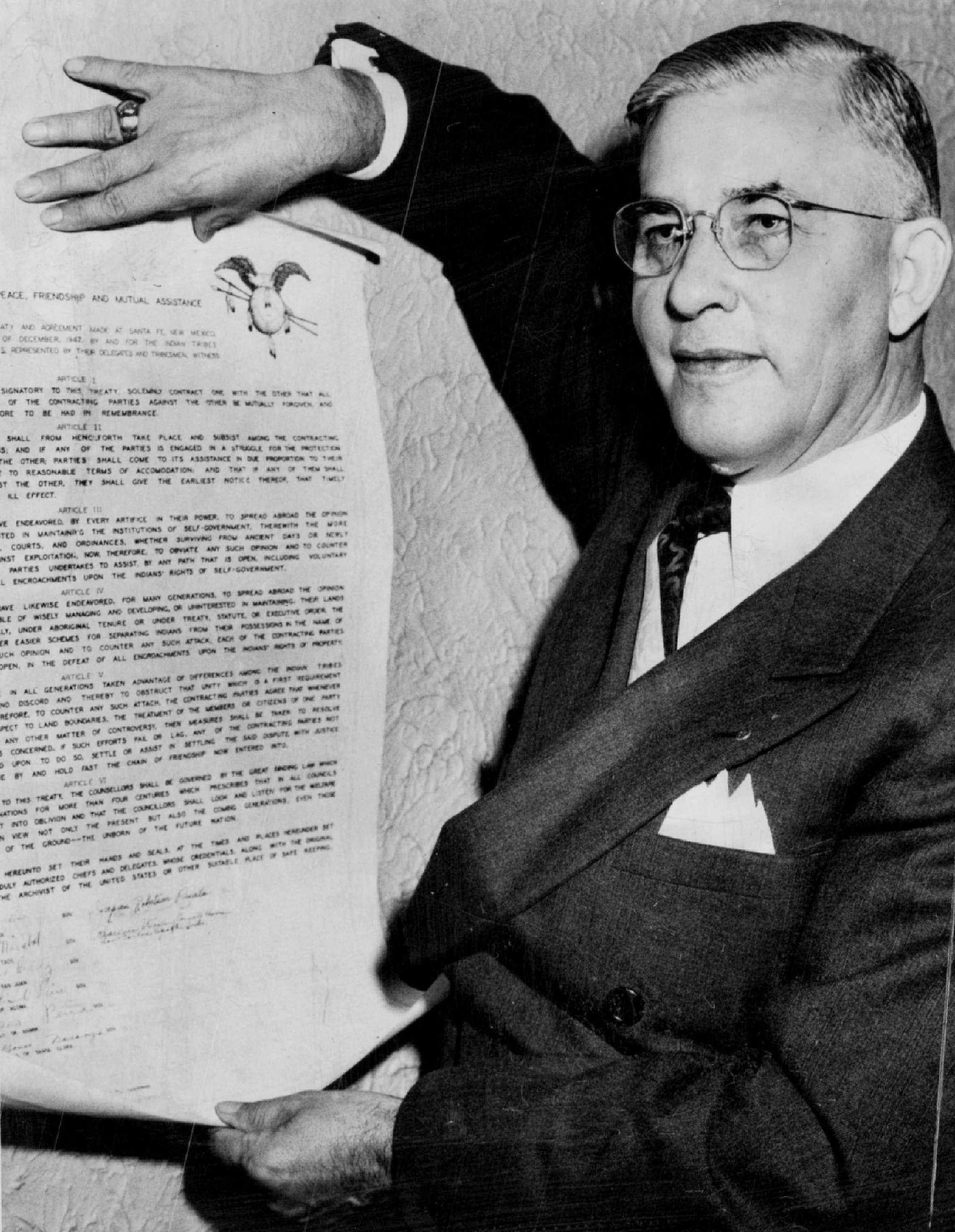

Upon closer inspection of the historical issues featured in The Sentinel, we learn that Pete Homer, then Chairman of the Colorado River Tribes, presented a unique document to the Santa Fe convention body–The Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Mutual Assistance. As he unrolled the scroll on which the treaty was inscribed, Chairman Homer stated, “This is a symbol of Indian unity and cooperation.” Pointing to the historic connections in the treaty, he noted, “We have had celebrated confederations of Indians in history working for common good. The Six Nations of historic fame, for example, remained united in purpose and efforts for a span of four centuries. In this day, we can do no less. This treaty proclaims the highest of ideals in community effort and purpose and reminds us eloquently of the high purposes for which we are united and organized in the National Congress of American Indians.”

This document, The Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Mutual Assistance was authored by NCAI leaders for several reasons. At the time, many people were spreading misinformed and racist beliefs that American Indians were not capable of, nor interested in, self-governance. The hope was that this treaty would disprove these lies, and would show the world a unified front and that all Tribal Nations were pledging to mutually protect and assist each other.

The Treaty was not only a legal document, but one that bonded Tribal Nations together against the forces that would deprive them of their rights, liberties, and lands. Pete Homer noted that the treaty’s vision was “ever fresh” and although it was modeled after historic treaties, it “embodied the wisdom of old counselors whose day on earth is done.”

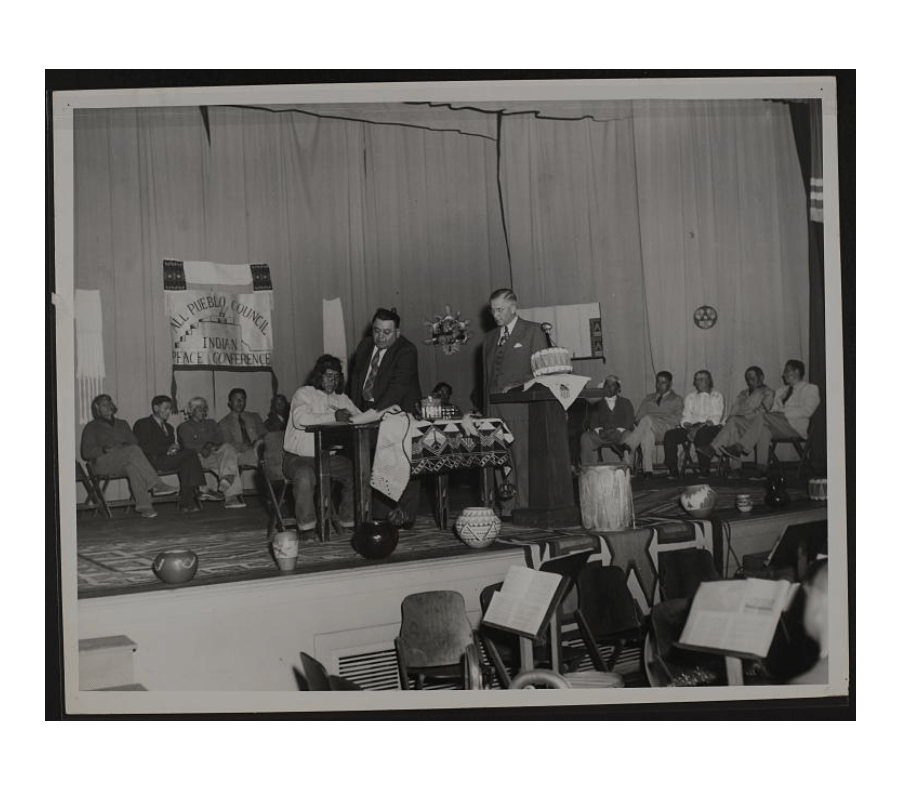

The first official signing of the treaty did not occur until April 11, 1948, by leaders of 19 Pueblos in New Mexico. At the ceremony held in Albuquerque, President Johnson gave an inspirational speech paying tribute to the Pueblo strength and resiliency. He called for greater unity not only among the Pueblos, but all Tribal Nations, and stressed the need for cooperation to combat outside forces threatening their very existence and well-being. He complimented the courage of the Pueblo people for being the first to sign the treaty. The ceremony included the presentation of a peace pipe and the beautifully adorned scroll with the treaty inscription.

Newspaper accounts at the time tell us that from Albuquerque, the treaty then traveled around the country to gather more signatures from tribal leaders. For example, on June 24, 1949, in Yakima, Washington, representatives from the Colville, Umatilla, and Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes assembled to sign the treaty. Joseph Garry (Coeur D’Alene) and Regional Secretary Frank George (Colville) presided at the ceremony. Both men later assumed positions of National leadership within NCAI–Joseph Garry serving as NCAI President from 1952 to 1960 and Frank George as Executive Director in 1952.

Many noted individuals were present at the treaty signing. Ninety-year-old Cleveland Kamiakin of the Yakama Nation, son of the famed Chief Kamiakin who signed a historic 1855 treaty with the Governor of Washington, affixed his thumbprint on the treaty. George Friedlander was also present, the great-grandson of Chief Joseph, leader of the Nez Perce Tribe.

While it has been challenging to assemble a complete record of the treaty’s journey, archival documents, and newspaper accounts from the time tell us that the treaty traveled around the country and was signed by additional Tribal Nations. And as with any great story, there is always a mystery– in this case, where is the actual treaty? Although contemporary documents state that it was to be deposited with the National Archives or the Oklahoma Historical Society after all Tribal Nations signed, neither repository has any record of that ever happening.

Even though researchers have not been able to locate the original treaty, its message and spirit live on. Tribal leaders, by drafting the treaty, joined together in a spirit of cooperation and unity, positioning themselves against threats to sovereignty and self-determination.

It is clear that the spirit of unity and resilience that guided NCAI in the 1940s is still very much alive today. The challenges may have evolved, but the focus remains the same: to defend the rights and interests of American Indian and Alaska Native communities. The lessons from history, as shared through stories like the Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Mutual Assistance, continue to inspire and guide our actions. This spirit of unity, this “One for All, All for One, United We Endure” ethos, continues to be NCAI’s driving force. Although the original treaty may be lost to time, its essence is very much a part of NCAI’s work today.

To learn more about the NCAI’s current efforts toward unity, sovereignty, and self-determination, visit http://www.ncai.org.