Signed into law on June 2, 1924 by President Calvin Coolidge, the Indian Citizenship Act, or Snyder Act, was a pivotal piece of legislation that granted citizenship to all American Indian people born within the limits of the United States. Although the 14th Amendment passed in 1868 granting citizenship to “All persons born or naturalized in the United States,” most American Indian people were excluded from the benefits of this amendment. It wasn’t until this legislation that they had a legal right to citizenship.

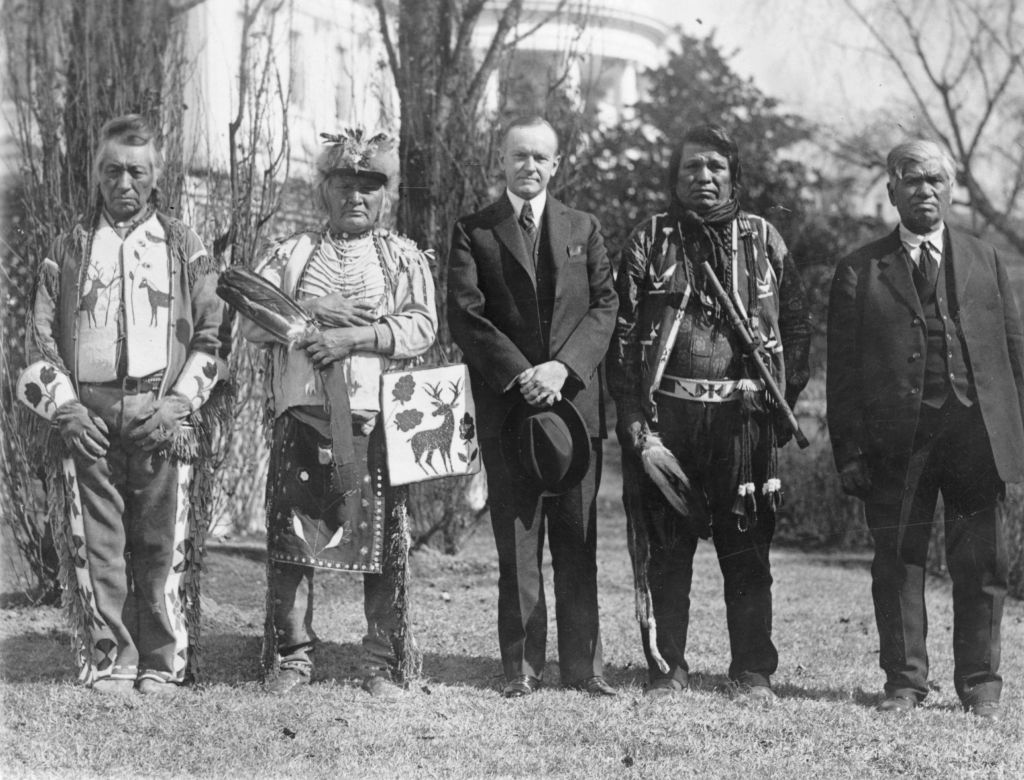

Although the signing of this legislation predates the formation of NCAI, the connections between the history of NCAI and this landmark event run deep. In 1923, Ruth Muskrat Bronson (Cherokee Nation), then a Mount Holyoke College student and young activist, attended a meeting of the “Committee of 100”, a group of scholars, activists, and policymakers. The Committee was tasked with advising the federal government on critical issues facing Indian Country. In December of that year, Ruth Bronson was invited to the White House by President Calvin Coolidge to give a speech. In her remarks, she stated, “We want to become citizens of the U.S. and have our share in the building of this great nation that we love. But we also want to preserve the best that is our own civilization.” Many claim that it was Bronson’s words that inspired President Coolidge to sign the Indian Citizenship Act into law the following year.

Ruth Bronson’s story does not end there. In 1945, she served as NCAI’s first Executive Secretary, holding that position until 1955. She then served as Treasurer from 1955 to 1957. Bronson also edited the organization’s policy newsletter, The Washington Bulletin, an early iteration of The Sentinel, and ran NCAI’s lobbying office in Washington, DC. She remained involved in a variety of roles within NCAI throughout the lifetime of her career.

Although Ruth Bronson’s words were a source of inspiration, the timing of the Indian Citizenship Act was a result of several factors. The country was fresh out of World War One, with approximately 15,000 Native Americans serving in the military. Many of these men were drafted by a country that would not grant them citizenship. The remainder of them volunteered for service for a country that refused them equal rights. The need to recognize their commitment and valiant service played a key role in the adoption of the Indian Citizenship Act. In addition, a growing civil and human rights movement in the early 20th century catapulted the legislation across the finish line. As the legislation was initially drafted, American Indians would have to apply for citizenship however President Coolidge modified the language to immediately confer citizenship upon all Native peoples.

Some saw The Snyder Act as a covert method to accelerate the assimilation of Native people into mainstream American society, by stripping them of their tribal identity in the process of granting them US citizenship. The irony is that even though self-governance was practiced in Native cultures for millennia before the formation of the United States, it took until the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act in 1924 for American Indian people to possess any legal basis for citizenship. Previously, citizenship was only obtained through piecemeal methods such as marriage to a US citizen, or by accepting individual allotments of land granted under the Dawes Act of 1887. However, it wasn’t until this pivotal legislation was adopted that the remainder of American Indians would now be legally granted their long overdue rights.

In theory, citizenship should confer an array of intrinsic rights such as voting. Nevertheless, even with the passing of this citizenship bill, Native people were still prevented from voting because the Constitution referred to the states to decide who had the right to vote. Thus, efforts to disenfranchise American Indian and Alaska Native people continued regardless of the law and persisted well into the 20th century.

Although the times have changed, similar barriers still remain. Many would argue the full rights of citizenship have never applied to American Indian and Alaska Native people. As the country approaches the Centennial of Indian Citizenship, we must also recognize that we are approaching another presidential election in November. NCAI and its allies will remain steadfast in the protection of Native peoples’’ civil rights to access the polls freely and without obstacles, remaining true to the original intent of the Indian Citizenship Act 100 years ago.